To cultivate the garden in such a way that the conditions for the growth of a living culture are set up.” – N. J. Habraken, 1972

Cultivating urban regions through design

In this era known as the Antropocene – a human-dominated geological epoch – urbanisation, ecological crisis and climate change are several of the societal challenges. These are demanding a fundamental review of the planning and design of its landscapes and infrastructures, in particular in relation to environmental issues and sustainability.[1] In order to redeem control over the processes that shape the built environment and its contemporary urban landscapes regional design can be employed as a powerful vehicle to guide spatial development and to re-establish the role of design as an integrating practice. This suggests more innovative and integral forms of urban landscape planning and design. Landscape-based regional design is considered an important strategy that shapes the physical form of regions using the landscape as the basic condition. It is an transdisciplinary effort to safeguard sustainable and coherent development, to guide and shape changes which are brought about by socio-economic and environmental processes, and to establish local identity through tangible relationships to a region. The regional design is like an open-ended strategy, aimed at protecting resources, guiding developments and setting up future conditions for spatial development by means of landscape planning and design.[2] This essay aims to introduce landscape-based urbanism and explores some backgrounds and approaches.

Plan Ooievaar (Stork) as proposed by De Bruin et al. (1987) offered a ground-breaking vision for the development of a river area in the Netherlands, in which ecological processes are the basis of shaping the landscape and creating conditions for sustainable water management and landuse. This plan provided the foundation for the recent Dutch ‘Room for the River’ programme, where measures are being taken to give the river space to flood safely, with projects at more than 30 locations (image courtesy of Dirk Sijmons)

The urban landscape as a complex system

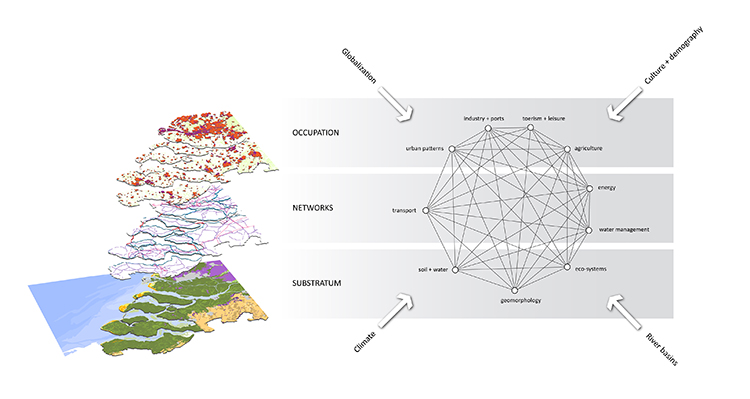

The urban landscape can be understood as a complex system composed of subsystems, each with their own dynamics and speed of change.[3] As a system the urban landscape is a material space that is structured as a constellation of networks and locations with multiple levels of organisation at different spatial and temporal dimensions.[4] Here the concept of the longue durée is essential: understanding the urban landscape as a long-term structure that is changing slowly. The first level of dynamics is related to the natural environment and is characterized by a slow, almost imperceptible, process of change, repetition and natural cycles. The second level of dynamics is related to the long-term social, economic and cultural history. The third level of dynamics is that of short-term events, related to people and politics.[5] In short, the urban landscape is an ongoing development resulting from action and interaction of both natural and human structures, patterns and processes that depend on ecological, socio-cultural, economic and political factors.

Landscape-based approaches in regional design strives to accommodate

spatial development via the application of principles of bioregional planning

and design that regard the urban landscape as a dynamic complex system. Landscape-based

approaches employ research methods, spatial organization models, planning and

design principles from landscape architecture, architecture, landscape

ecology and geography, but also uses insights from systems thinking and

complexity theory to engage into a more

comprehensive form of regional planning and design that addresses the complex

webs of relationships constituting the urban landscape. As such the regional

design provides spatial means for urban transformation, biodiversity

protection, water resource management, recreation, community building, cultural

identity and economic development.[6]

Understanding the urban landscape as a layered and complex system (Image: S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

Characteristics of landscape-based regional design

What is the particular nature of landscape-based regional design? The presumption is that the answer can be found in a set of characteristics that make up this form of urban landscape architecture. Landscape-based regional design determines or guides the most beneficial location, function, scale, and inter-relationships for sustainable development of a region (strategy), as well as setting the scene for local projects (intervention).[7] It does that through design research and research-through-design as research strategies to explore the possibilities and identify the potentials for multi-scale spatial development. Mapping and drawing are thereby important tools for visual thinking and communication.[8] The regional design shapes the physical form of regions based on the physiology of the natural and urban landscape and is about creating conditions for future development. It establishes robust and adaptive systems, which are open to change. In order to grow and develop such kind of systems both must persist and adapt; its organisational structures must be sufficiently adaptive to withstand challenges, while also supple enough to morph and reorganise.[9]

Landscape-based regional design works through the scales from regional

to local, from general to specific, and maintains overall continuity as well as

facilitates local contingency. This offers ways of balancing out services and

qualities between parts of a territory.[10] Landscape-based regional design

recognises the collective nature of the urban tissue and allows for the participation

of multiple authors. The regional design creates a directed field where

different stakeholders and other participants can contribute.[11] In that

respect landscape-based regional design is a transdisciplinary effort where

specialisations in engineering and ecology blend with spatial design thinking

but also includes the ideas and knowledge of inhabitants. As such the regional

design can be considered an integrative and innovative platform that organises

physical structures (“hardware”), people

and knowledge (“software”), governance

(“orgware”) and their interaction

through space and time at different scales.

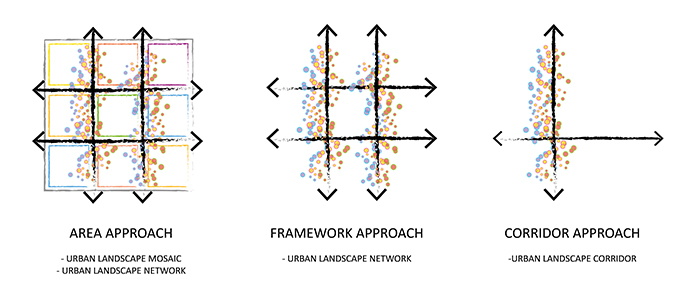

Landscape-based design approaches (schemes by S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

Landscape-based regional design approaches

In the practice of landscape-based regional design three types of approaches can be identified that enable to establish characteristic relationships between structure and process throughout the scales: area, framework and corridor approaches. Area approaches provide for a landscape mosaic in which zones for long-term, sustainable conditions for ‘low dynamic functions’ (network) are created as well as expanses of land in which ‘high dynamic functions’ may flourish (mosaic). Examples include Plan Stork (The Netherlands) and Masdar City (Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates). Framework approaches provide for long-term and coherent landscape networks of landscape structures to support spatial development, safeguard resources and spatial coherence and create conditions for local developments. Examples include the Boston Metropolitan Park system (USA) and the Emscher Park (Ruhr-area, Germany). Corridor approaches provide for, or develop, supporting landscape structures as armatures for urban and rural development that direct, facilitate and create conditions for urban development, stimulate social and ecological interaction. Examples include: Rio Madrid (Spain) and The High Line (USA).

Urban landscape infrastructures is

an emerging regional design concept that explores infrastructure as a

type of landscape and landscape as a type of infrastructure.[12] The

hybridisation of the two concepts, landscape and infrastructure, seeks to

redefine infrastructure beyond its strictly utilitarian definition. Urban

landscape infrastructures are considered to be operative structures that

direct, facilitate and create conditions for urban development, stimulate

social and ecological interaction and establish the relation between process

and form. They are landscape infrastructures for (1) provision of food, energy,

and fresh water; (2) support for transportation, production, nutrient cycling;

(3) social services such as recreation, health, arts; and (4) regulation of

climate, floods and waste water in the urban landscape. The design of these

operative landscape infrastructures is a crosscutting field that involves

multiple disciplines in which the role of designers as integrators is

essential. There are three potential fields of operation: transport, green and

water landscape infrastructure, which need to be explored on their opportunities

and possibilities for strategic regional design and local interventions.

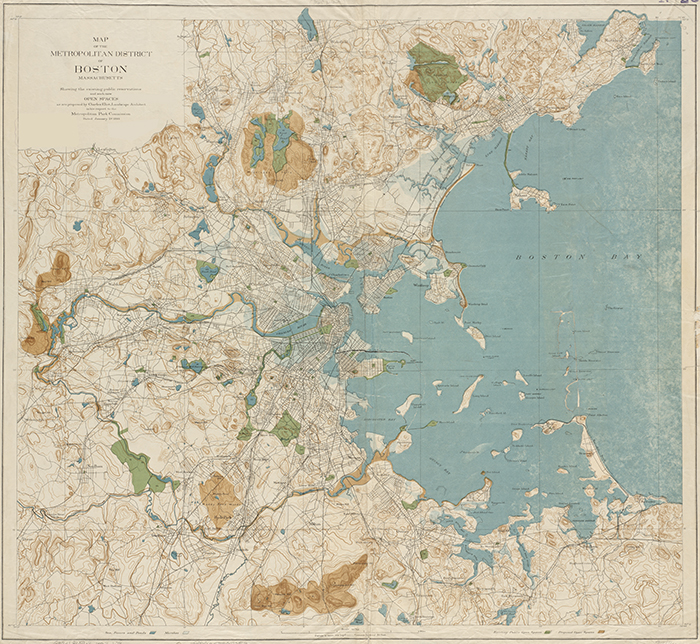

The Boston Metropolitan Park System as proposed by Sylvester Baxter and Charles Eliot in 1893 offered a new vision for how a green-blue system could function as an armature for the rapidly expanding metropolitan area of Boston (Massachusetts, USA). The plan exemplifies the potential to shape urban and architectural form while employing social and ecological processes to establish a local identity that has tangible relationships to the region (image source: personal archive, Steffen Nijhuis)

In conclusion

As discussed, the urban landscape is the result of different processes and systems that influence each other and have different dynamics of change. The ability to interrelate systems through spatial design becomes increasingly important, as the complex interconnection of different systems and their formal expression is a fundamental aspect of contemporary regional development. Landscape-based regional design is an important vehicle to gain operative force in territorial transformation processes while establishing local identity and tangible regional relationships through connecting ecological and social processes, and urban and architectural form. It stimulates design disciplines like architecture, urban planning and landscape architecture to cooperate and review the agency of spatial design giving shape to the built environment, and establishes relationships between ecology and socio-cultural aspects, between process and form, between long-term and short-term development, between the space of flows and the space of places. In this perspective landscape-based regional design provides spatial design – as an integrative, creative activity – a new operational power and acknowledges the regional urban landscape as an important field of inquiry that is context-driven, solution-focussed and transdisciplinary.

Further reading

To download:- Nijhuis, S, & Jauslin, D (2015) Urban landscape infrastructures. Designing operative landscape structures for the built environment. Research In Urbanism Series, 3(1), 13-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.7480/rius.3.874

- Meyer, H, Bobbink, I, & Nijhuis, S (eds.) (2010) Delta Urbanism. The Netherlands. Chicago & Washington: American Planning Association (ISBN 978-1-93236-486-6) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287331026_Delta_Urbanism_The_Netherlands

- Meyer, H, Bobbink, I, & Nijhuis, S (eds.) (2010) Delta Urbanism. The Netherlands. Chicago & Washington: American Planning Association (ISBN 978-1-93236-486-6)

- Meyer, H. & Nijhuis, S (2016) ‘Designing for Different Dynamics: The Search for a New Practice of Planning and Design in the Dutch Delta’ , in: Portugali, J, & Stolk, E. (eds.), Complexity, Cognition, Urban Planning and Design, Springer Proceedings in Complexity, 293-312. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32653-5_16

-

Meyer, H & Nijhuis, S (2013) Delta urbanism: planning and design in urbanized deltas – comparing the Dutch delta with the Mississippi River delta. Journal of Urbanism 6 (2); 160-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2013.820210

Notes

[0] This essay will be published as: Nijhuis, S (2019) ‘Cultivating urban regions through design’, in: Cattaneo, E, & Rocca, A. (eds.) Future landscapes. European experiences in landscape design and urbanism. Politechnico Milano, Dipartimento di Architettura e Studi Urbani / Regione Lombardia (in press)

[1] Crutzen, P. (2002) Geology of mankind. Nature 415: 23

[2] Nijhuis, S., & D. Jauslin (2015) Urban landscape infrastructures. Designing operative landscape structures for the built environment. Research In Urbanism Series, 3(1), 13-34. DOI:10.7480/rius.3.874.

[3] Meyer, H. & S. Nijhuis (2013) Delta urbanism: planning and design in urbanized deltas – comparing the Dutch delta with the Mississippi River delta. Journal of Urbanism 6(2): 160-191.

[4] Doxiadis, C.A. (1968) Ekistics. An introduction to the science of human settlements. New York, Oxford University Press;

Otto, F. (2011) Occupying and connecting. Thoughts on territories and spheres of influence with particular reference to human settlement. S.l., Edition Axel Menges; Batty, M. (2013) The new science of cities. Cambridge (Mass.), The MIT Press

[5] Braudel, F. (1966) La Medtiterranee: La part du milieu. Paris, Librairie Armand Colin

[6] Neuman, M. (2000) Regional design: Recovering a great landscape architecture and urban planning tradition. Landscape and Urban Planning 47, 115-128

[7] Nijhuis & Jauslin 2015 (note 2)

[8] Nijhuis, S. (2013) ‘New Tools. Digital media in landscape architecture’, in: Vlug, J. et al. (eds.) The need for design. Exploring Dutch landscape architecture. Velp, Van Hall Larenstein, University of Applied Sciences, 86-97

[9] Corner, J. (2004) Not unlike life itself. Landscape strategy now. Harvard Design Magazine 21: 31-34

[10] Busquets, J. & F. Correa (eds.) (2006) Cities X Lines. Approaches to City and Open Territory Design. Nicolodi Editore

[11] Allen, S. (1999) ‘Infrastructural urbanism’, in: idem, Points + Lines. Diagrams and Projects for the City. New York, Princeton Architectural Press, pp. 46-59

[12] Nijhuis & Jauslin 2015 (note 2)