The face of landscape

Landscape can be defined as “an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors.” [1] This definition clearly emphasises the sensory relationship between the observer and the landscape. The major question here is: how do we know and understand the landscape through perception?

Although ‘perceived by people’ refers to a holistic experience with all senses, very often it is reduced to the visual aspects. This has to do with the fact that 80% of our impression of our surroundings comes from sight. [2] Also the ‘range’ of our senses plays an important role. Granö (1929) already made the distinction between the ‘Nahsicht’ and ‘Fernsicht’. The Nahsicht or proximity is the environment we can experience with all our senses, the Fernsicht he called also landscape and is the part of our environment we mainly experience by vision [3]. Hence the identifying character of landscapes in the rural and urban realm is, to a large extent, built upon visual perception. Since visual perception is a key factor in behaviour and preference, it is crucial for landscape planning, design and management, as well as for monitoring and protection of landscapes. But how can we comprehend the ‘face of the landscape’ and its perception? And how can we make this applicable to landscape planning, design and management?

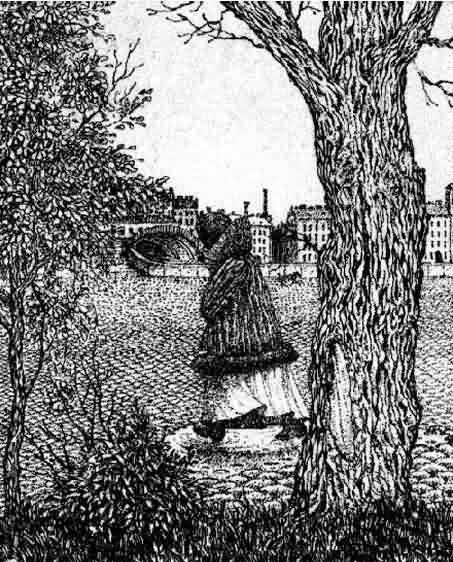

Can you see the face? [4]

Visual landscape research

We believe that the long tradition and current advances in the field of visual landscape research offer

interesting clues for theory, methodology and applications in this direction [5].

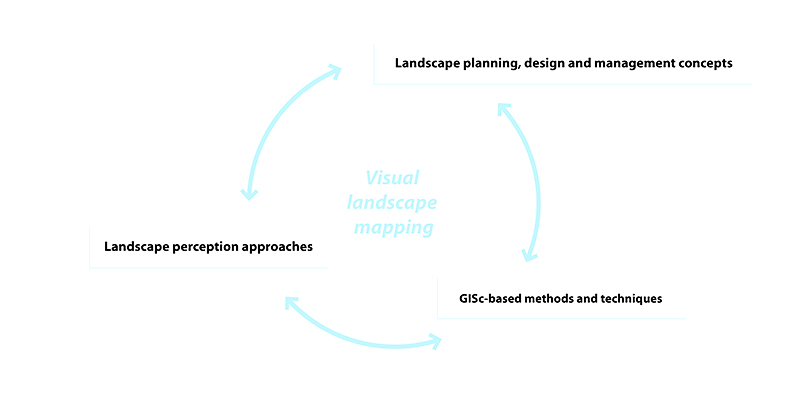

Visual landscape research is an interdisciplinary approach that combines (a) landscape planning, design and management

concepts, (b) landscape perception

approaches, and (c) Geographic

Information Science (GISc)-based methods and techniques. While integrating psychological

knowledge of landscape perception, the technical considerations of geomatics,

and methodology of landscape architecture and urban planning, it provides a solid

basis for visual landscape assessment in cities, parks and rural areas. It

offers great potential for the acquisition of design knowledge by exploring

landscape architectonic compositions from the ‘inside out’, as well as

possibilities to enrich landscape character assessment with visual landscape

indicators. Since they are crucial elements in landscape perception and

preference it is important for landscape planning, policy and monitoring to get

a grip on visual landscape attributes like spaciousness and related indicators

(e.g. degree of openness, visual dominance, building density and the nature of

spatial boundaries).

Visual landscape research is characterized by visual landscape mapping an determined by the integration of landscape planning, design and management concepts, landscape perception approaches and GIS-based methods (image S. Nijhuis, TU Delft)

The field of visual landscape research is expanding every day. Influenced by national and international initiatives it is likely to continue developing in three ways. In the first place by scientific development of theory, methods and techniques. Secondly by implementation in education, and thirdly by knowledge transfer and applications in academia and society (valorisation). In order to facilitate this development a dialogue is needed between the scientific community and society through high quality publications and platforms for knowledge dissemination and discussion. We like to contribute to this dialogue via our platform Exploring the Visual Landscape (EVL), an initiative of Delft University of Technology, Landscape Architecture and Wageningen University, Centre for Geo-Information.

Further reading

To download:- Nijhuis,

S, Lammeren, R van & Hoeven, FD van der (eds.) (2011) Exploring the Visual

Landscape. Advances in Physiognomic Landscape Research in the Netherlands. Amsterdam: https://doi.org/10.7480/rius.2

- Nijhuis,

S (2011) Visual research in landscape architecture, Research

in urbanism series, vol. 2; 103-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.7480/rius.2.209

- Nijhuis,

S, Lammeren, R van, Antrop, M (2011) Exploring visual landscapes. An

introduction, Research in urbanism

series, vol. 2; 15-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.7480/rius.2.205

- Nijhuis,

S & Reitsma, M (2011) Landscape policy and visual landscape assessment. The

Province of Noord-Holland as a case study, Research

in urbanism series, vol. 2; 229-259. http://dx.doi.org/10.7480/rius.2.214

- Nijhuis,

S & Van der Hoeven, F (2018) Exploring the skyline of Rotterdam and

The Hague. Visibility Analysis and Its Implications forTall Building Policy. Built Environment 43(4), 571-588. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.43.4.571

-

Tisma, A, Velde, JRT van der, Nijhuis, S & Pouderoijen, MT (2014) A method for metropolitan landscape characterization; case study Rotterdam. SPOOL journal, 1(1); 201-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.7480/spool.2013.1.637

- Van

der Hoeven, F & Nijhuis, S (2011) Hi Rise, I can see you! Planning and

visibility assessment of high building development in Rotterdam, Research in urbanism series, vol. 2;

277-301. http://dx.doi.org/10.7480/rius.2.216

Notes

[1] Council of Europe (2000) European Landscape Convention. Florence. European Treaty Series 176. p3

[2] Seiderman, A., Marcus, S. (1989/1991) 20/20 is not enough. The new world of vision. New York. Alfred a. Knopf. p6

[3] Granö, J.G. (1929) Reine Geographie. Eine methodologische Studie beleuchtet mit Beispielen aus Finnland und Estland. Acta Geographica 2 (2); 202. Recently republished in: O Granö and A. Paasi (eds.) (1997) Pure Geography. Baltimore and London, The John Hopkins University Press.

[4] Source: http://www.newopticalillusions.com/3d-optical-illusion/face-optical-illusion-2/ [accessed: February 4th, 2012]

[5] See for an overview: Nijhuis, S, Lammeren, R van, Antrop, M (2011) Exploring visual landscapes. An introduction, Research in urbanism series, vol. 2; 15-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.7480/rius.2.205